THE PLURALIST – Issue 4

Edited by Rachel Yalisove and Niyoshi Shah

Designed by Celine Strolz, Eilis Searson and Will Bindley

CONVERSATION WITH OLIVIA BAX, Ann Kim

When I see one of your works, I know that’s Olivia Bax. There’s such a signature about it, whether it’s the pulp that’s so critical to your practice or your colour palette. Can you talk about finding those signature things, those key footholds as an artist?

A lot of where things come from is circumstantial, I suppose – how do you make within your means, what can you physically lift, what can you make within your physical space.

I always think that hands are the most readily available tool. I like sculptural processes – the idea of needing a tool to make something, or needing a jig to fit something in place, or needing a certain device in order to do the thing that’s in your head. And for me, the hand is just the best way. It’s like trying to make a meal when you’ve only got three ingredients in your fridge. The hand gesture has become a kind of mark because it’s the thing I can always use when I don’t have anything else. That’s the signature, if you like. And it’s not just about an arbitrary texture anymore, it’s how the thing has come to be.

You were asking about material…You’re right, the pulp has become really important but that’s something I’ve fashioned, again, out of circumstance. What can I make in mass, quickly, that’s light and has these kind-of squishing properties? Well, I pass free newspapers on the tube so I can collect them in my rucksack and take them back to the studio.

You cover your materials with this pulp and with your handwork but I can still kind of tell what the original interior is. I often feel conflicted about covering up materials, do you?

Totally. I have constant conversations in my head about the role of an armature (which for me feels like the beginning of an idea or the facilitator of anything you want to make) and the covering process. In the earlier pulped works, the armature was polystyrene, which is not a material that lasts. I didn’t feel any conflict covering it, because, when the pulp dried, it made the armature solid so that the polystyrene wouldn’t disintegrate. But more recently, I’ve been less interested in polystyrene, and I’ve gone back to exploring frameworks of steel and other more robust material. Then I have a real conflict because I don’t want to cover what the material is. So, I’ve been playing around a lot more with having the armature as a facilitator and then using these quick, spontaneous actions in a way that’s not completely covering what it started out as– just changing the speed of making. I really like that– labouring on something and then for one spontaneous action or quick decision, changing the approach in the studio. That for me is what everyday life is like as well. You spend a long time trying to achieve something and then– bam, it’s there. I like replicating those kinds of moments physically.

Going back to what you were saying about covering – It is physically covering one material with another material, but I also see it more as understanding what that initial action is. I draw all the time and something I notice about the way I sketch is that I might draw a form and then I’ll re-draw over the bits of the shape that I liked – like how you would highlight an essay. It’s about reaffirming in your head, ‘Well, I made that decision and what was it about that decision that I liked?’

I can definitely see how drawing informs your work– like tracing and retracing, first with the pencil and then with your hands. Can you tell me a bit more about the role that drawing plays within your practice?

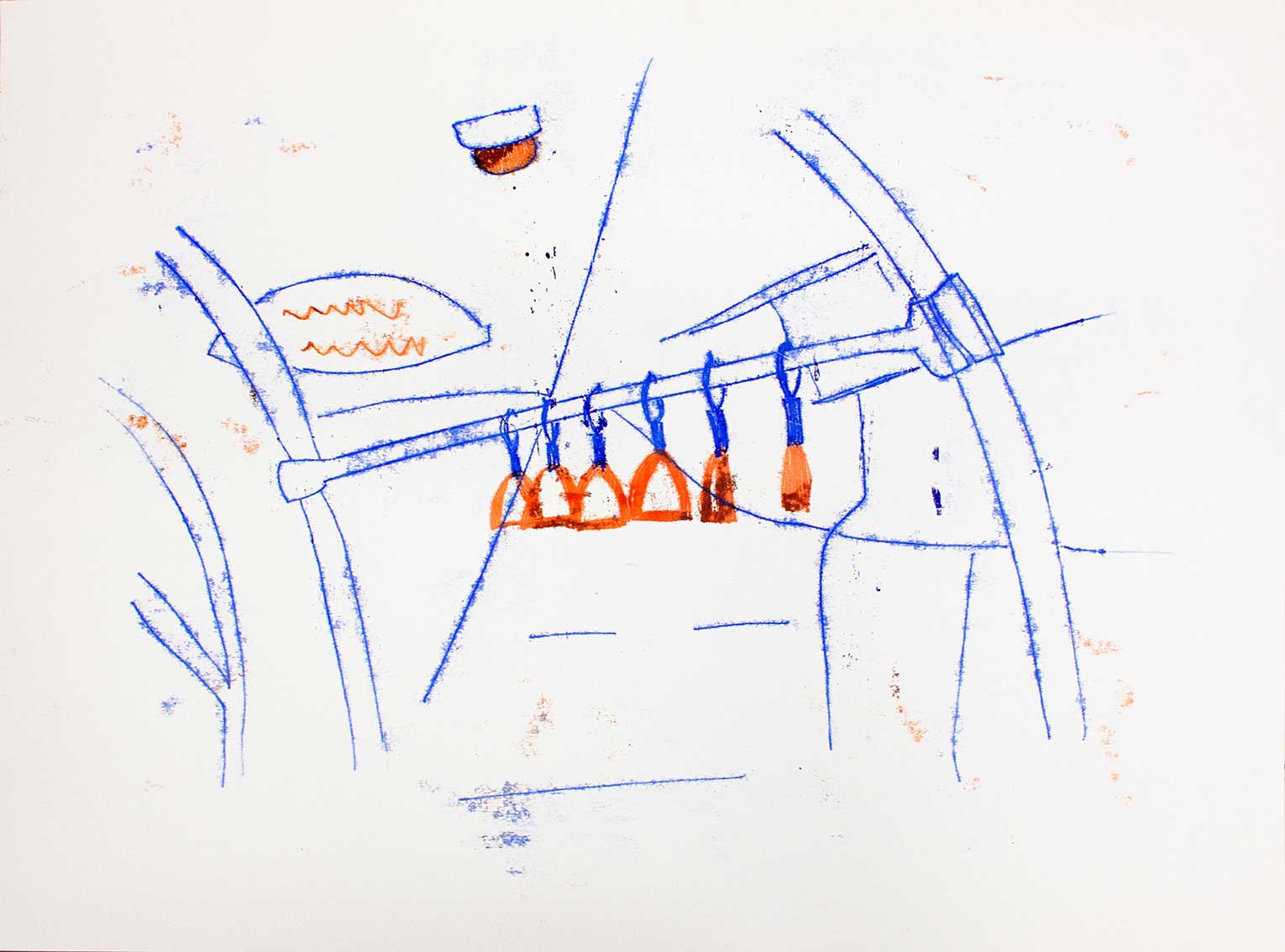

I quite often see things when I’m out and about like a form or a shape or a point of tension. I used to take photos of those things and then print them out for my studio wall as a sort of reminder. Now I’m trying not to do that. I’m trying to draw what I see because then I have to think about what I’m looking at.

And I’ve always liked the word ‘sketch’ as opposed to ‘drawing’. There’s something so immediate and raw and fresh about a sketch that nobody ever sees and being able to make sculpture with that energy is always a challenge.

What else do you do outside of the studio to refill the well?

Recently, I’ve been lucky in that I’ve done a few residencies which have been really fruitful– one after I left the Slade, to Hong Kong, and one when I was at the Slade, to Dhaka in Bangladesh. I think removing yourself from your everyday habits and ordinary life gives you perspective. You see things that you ignore when you’re in a routine. The residency in Hong Kong was this time last year, and I would say, all the work I’ve made since has been directly inspired by moments and observations from that experience.

I heard that when you were Anthony Caro’s assistant he said, ‘Stop making sculpture, create a world.’ How did you unpack those words for yourself?

I think I took my whole Master’s trying to unpack that phrase and now I’ve come to the conclusion that of course it’s your world if you’ve made it, and it’s hard not to make your world actually– when you’re dealing with objects and space and three-dimensionality. At the time it seemed so profound but now it feels like more of a given.

The sculptures I make are independent things and they could be seen independently, but I’ve worked out and established that what I really like is when I have a whole space so that the objects can breathe by themselves, and then it becomes about interaction with the other things. If I’ve assembled a sculpture, I think to myself, ‘Oh, maybe I need to make another sculpture so that I see this sculpture through thats culpture.’ That’s how it’s become more ‘worldly’.

The work I make is often fed from the piece I made before. All the time I’m fluctuating between different mediaand processes. I think of it more as a lineage– they’ve become bodies of work that can be independent but they’re more successful when they’re together.

Are there other things that Anthony Caro said that you’ve returned to? What were some other things you learned from him?

Absolutely. His attitude was probably the most inspiring. He was in the studio every day. He had bad days and good days, but when he was struggling with something, he would just start something else, leave things for a bit, and come back to it. I found the way he worked in series inspiring too. I always had this sense that he was trying to explore a series to its fullest potential. I also witnessed how difficult it was for him to edit at the end of that process when putting on shows – and I’m super aware of that with my own work now. Sometimes I make things really quickly, and sometimes it takes time, but just because it is there does not mean it is enough. Learning how to scrap something is so hard.

My work changed so much in the three years that I worked with him. When I first started my preferred material was steel, but I got curious about other materials – probably because I was around steel all the time.

I found it interesting that he didn’t really care about how materials were joined. He was like a composer. He was very good at directing people and material to make a composition, but whether that bit of steel was bolted or welded wasn’t really a concern. Those were the questions I was asking the whole time I was there, and that became the important thing for me in my studio – what’s the most outrageous way of joining two materials, and how can I really exaggerate the way it’s fixed? That’s still something that’s stayed with me.

I find myself struggling with form at the moment. Sometimes it feels like I’m making with a viewer in mind, or performing for a future audience. Do you ever struggle with form? Where does thinking about form fit into your process?

Sometimes it’s easier to avoid thinking about that altogether. In some of my assembled pieces, I’m almost ignoring the form until the last possible minute. I create a sort of toolkit of things, and then the form comes out of arranging those things, and the spatial experience between me and the work, and what’s physically possible. When you assemble something, it either surprises you, which is the best possible outcome, or it doesn’t work and you can’t quite understand it. So I suppose you’re hoping for that surprise. I like the challenge of form being the last thing you have to address, because it is the hardest, and it’s the thing that will hopefully pin everything together and make something work.

Having said that, the stuff I’m making right now isn’t assembled, and I’m trying to make the sculpture more self-standing and singular. You need to challenge yourself all the time – is it too easy just having parts and then sporadically putting them together? What happens when the armature or the form is set and I reverse my process? Can I still create that energy within an object doing it the other way around?

What do you do when you’re stuck?

I might revisit a work that I had packed away. (To get clarity in my head, I think, ‘Would I ever show that?’ and if the answer’s no, but I don’t know how to change it, I put it away). I just took something out that was in this category. I made a wall work last year (Loop da Loop), but the six-month gap had made me completely un-sensitive to it, and I wasn’t sentimental about keeping it, so I could destroy it in a way that made it much more interesting, and now it’s hanging on the studio wall. It is still not a piece that I would show, but now it’s become a helpful device, because there are moments in it that are interesting. It’s the way I wrapped something, and I can use that later. Now the sculpture has been a learning experiment, and it’s probably an object that will kick around my studio for ages because it will remind me of that development.

Or I draw. I love quick sketches. And if something’s still not clicking, I go out to a museum or a show, and it’s always the ones you don’t expect that inspire you. I think artists beat themselves up when things aren’t going that well in the studio. You can’t do it every day. Sometimes you need to get out of yourself –and the work – to refresh.

I also always find it easier when I am working towards a specific exhibition. All the experimental research that’s happening in the studio then becomes more concrete. Before then, it just feels like you’re making decisions to help yourself later for when something concrete presents itself.

Going back to that piece you’re keeping because it’s reminding you of the way you wrapped something – It’s interesting how an entire sculpture can be reduced down to one little gesture that appears in the next adaptation, how you were meant to create that in order to find that one little thing.

Absolutely. It can be frustrating because, you’re like, do I have to do all that work to get to that point – but you could never have found it otherwise. And then sometimes it’s even more annoying when you try and replicate it, and it’s impossible, and you realise that it just has to belong in that one little object.

What are some qualities that might make a good maker?

I think that people who are empathetic have a really good understanding of sculpture. Empathy is about understanding different points of view and seeing in different directions. Making sculpture requires an understanding about materials and objects from different angles. People who are good makers must be first of all good observers to notice things.

What are the things that you wish you’d known while you were in school?

The best thing about studying is that you can try things to the extreme. You can go too far one way and then too far the other direction in order to find your feet. I tried to make really crude and ugly work at the beginning of my second year to ‘see how it felt’. I don’t think one can take those sorts of steps outside the protection of institutional walls. But now that I have tried it I feel like I have the confidence to explore those territories on my own… So, my advice would be to push hard in every direction, while you can!

________________________________________________________________________

Olivia Bax lives and works in London. She completed her MFA Sculpture from Slade

School of Fine Art (2016). Recent exhibitions include: A Motley Crew, Christian Larsen

Gallery, Stockholm (2017), Concrete & Clay, Roaming Room, London (2017), Hands On, Academy of Visual Arts, Hong Kong (2017) and a solo show ZEST, Fold Gallery, London (2016-2017). Residencies and awards include: Artist-in-Residence, Academy of Visual Arts, Hong Kong Baptist University (2016-2017), Additional Award, Exeter Contemporary (2017), Kenneth Armitage Young Sculptor Prize (2016) and Public Choice Winner, UK/Raine, Saatchi Gallery (2015). Olivia and Jean-Philippe Dordolo are the Art Editors for the quarterly magazine AMBIT (ambitmagazine.co.uk).

oliviabax.co.uk / @olivia_bax_